By Blaine Harden

Published: February 18, 2001 in the New York Times Magazine

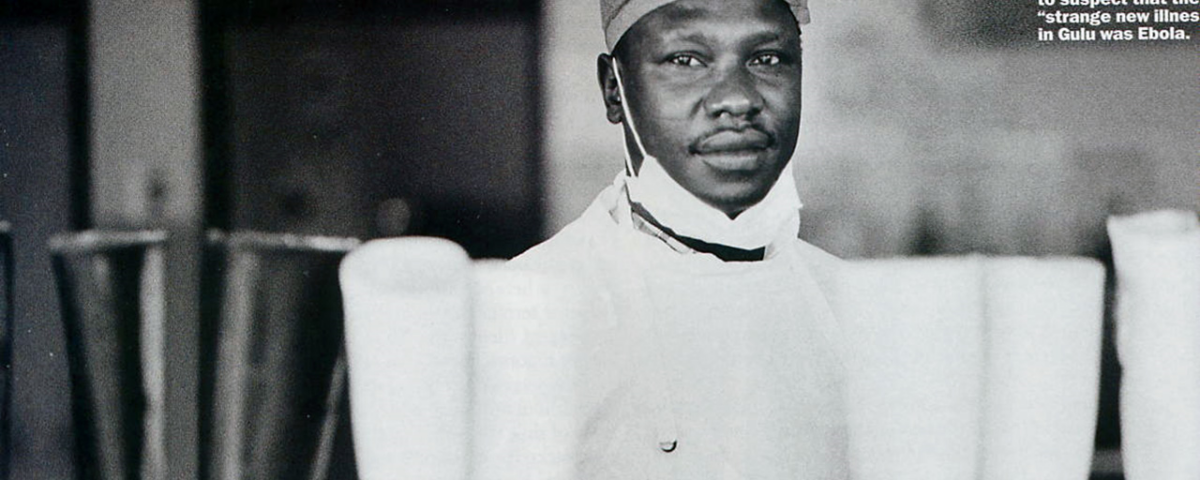

In the last few hours before he died, Simon Ajok seemed to explode ‐‐ first in blood, then in aggravation.

The burly male nurse, who had contracted Ebola while caring for patients in an isolation ward at St. Mary’s Hospital in northern Uganda, was wearing an oxygen mask when he started to hemorrhage. The oxygen had turned his blood bright red. It saturated the whites of his eyes and swelled his eyelids to near‐bursting. He began to bleed profusely from his nose and gums. Fighting to breathe, Simon ripped off his oxygen mask. He coughed violently, spraying a fine mist of mucous and blood onto the wall beside his bed.

Then, to the astonishment and terror of the night‐shift staff in the Ebola ward, the 32‐year‐old nurse hauled himself out of bed. Coughing blood and muttering angrily, he lurched out of his private room and into the long hallway of the ward. Simon had pulled loose from his catheter. An IV tube dangled from his arm.

Babu Washington Stanley was a nurse on duty that night. As he would later recall, he and others on the ward retreated down the corridor while he shouted, ”Please, Simon, go back!” They were covered head to toe in protective gear ‐‐ rubber boots, gowns, aprons, gloves, masks, head caps and plastic eye shields. But they had never seen a critically ill Ebola patient behave like this.

Biomedical researchers admit profound ignorance about Ebola, a viral bleeding fever that first appeared in Africa in the late 1970’s. There is no cure, and researchers do not know where the virus hides between human outbreaks. They do know, though, that the blood of an acutely ill Ebola patient is one of the most infectious and deadly substances on earth.

The Ebola epidemic that broke out last fall in Uganda and lasted until January was the largest ever. More than 400 people were infected; 173 died. But the patients there, even those who died, did not suffer the massive and uncontrollable bleeding from nearly every orifice that has made Ebola the dark star of the world’s infectious diseases. That is, until the night Simon Ajok erupted.

The Ebola epidemic that broke out last fall in Uganda and lasted until January was the largest ever. More than 400 people were infected; 173 died. But the patients there, even those who died, did not suffer the massive and uncontrollable bleeding from nearly every orifice that has made Ebola the dark star of the world’s infectious diseases. That is, until the night Simon Ajok erupted.

”Please, Simon, go back!” Babu Washington Stanley shouted again that night, as his wildly agitated colleague stood bleeding in the hallway. Not knowing what else to do, the nurse did what everyone at the 500‐bed hospital had done for years, whenever things got out of control. At 5 a.m. on Nov. 20, he called Dr Matthew Lukwiya.

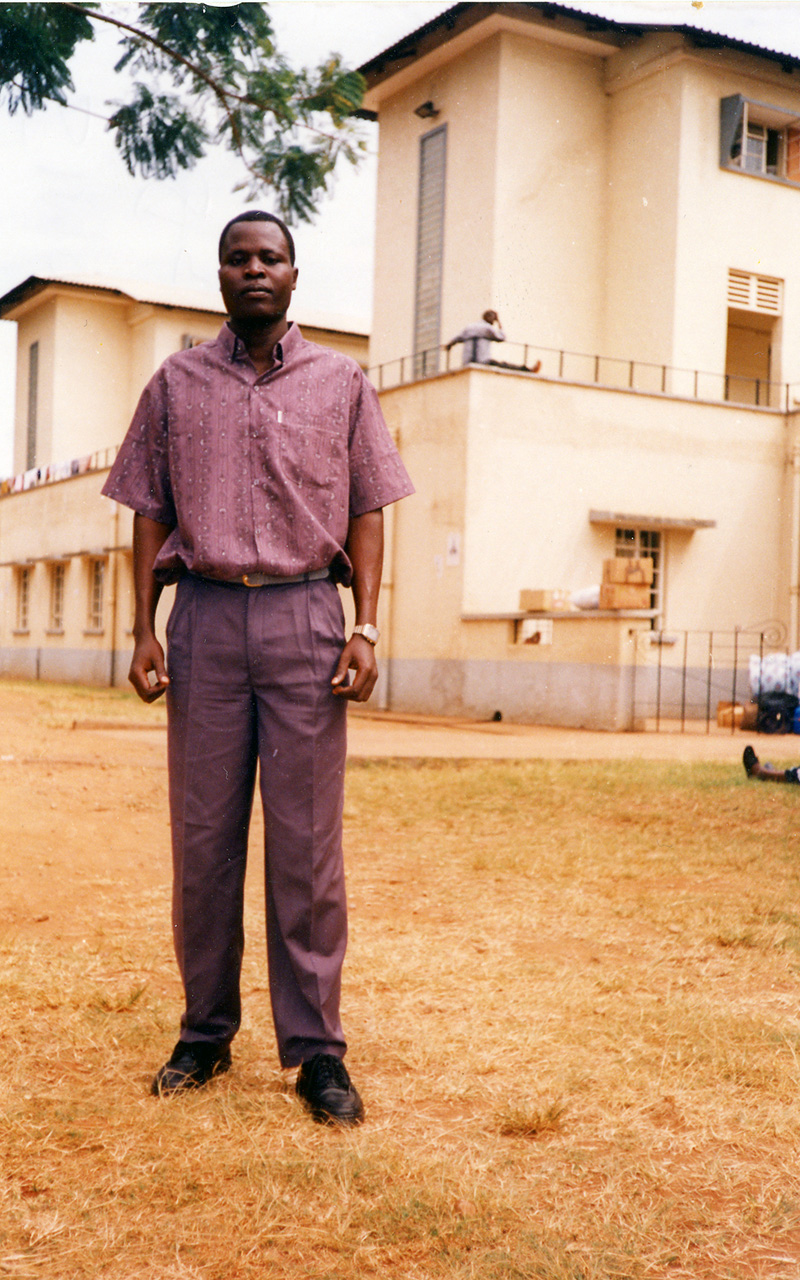

Dr Matthew, as he was known to his colleagues and patients, was the hospital’s medical superintendent. He had helped make it one of the best medical facilities in East Africa. He was also a home‐grown hero in the scrub savanna of northern Uganda.

Children playing in the dust‐blown streets of Gulu, a city a few miles from St. Mary’s Hospital, had for years been singing a little ditty about the doctor. In it, they dared each other to jump from a high place. A broken leg would not be a problem, they sang; Dr Matthew would fix it.

In his 17 years at St. Mary’s, a Catholic missionary hospital, much of what Dr Matthew fixed had nothing to do with medicine. A soft‐spoken, deeply religious man of 42, with a wide, easy smile and a slight paunch, he had stood up to a bizarre bunch of local rebels called the Lord’s Resistance Army. They said they wanted to run Uganda according to the Ten Commandments. But what they had done for 13 years was kidnap thousands of children and press them into suicidal duty as soldiers. The rebels also abducted and mutilated adults, often slicing off their lips and ears.

When rebels came to the hospital in 1989 to kidnap some Italian nuns living there, Dr Matthew (who was an evangelical Protestant, not a Catholic) met them at the front gate and persuaded them to take him instead. He marched around in the bush for a week in his doctor’s gown before the rebels let him go. He later opened the walled compound at St. Mary’s as a sanctuary from the rebels. Until Ebola scared them away, about 9,000 people entered the grounds of St. Mary’s every evening to sleep in peace.

The panicked call from Nurse Stanley roused Dr Matthew from his bed. His small house was located inside the hospital compound, and the doctor made it to the Ebola isolation ward within five minutes. He suited up, as always, in boots, gown, apron, head cap, gloves and mask. He neglected, however, to put on goggles or a plastic face shield, which can protect the eyes when an Ebola patient coughs. Perhaps he was still groggy from sleep.

Simon Ajok

Simon Ajok had by then stumbled back to bed, where he was gasping for breath in his private room (one of the meagre privileges afforded health‐care workers who caught Ebola at St. Mary’s). To help him breathe, Dr Matthew pulled Simon, who was sticky with blood, into a sitting position. He then cleaned him up, stripping off his soaked gown and changing the soggy sheets on his bed. Simon died while the doctor was mopping the floor with bleach.

When he finished cleaning up, Dr Matthew went back to his house, ate some breakfast and then put in another 14‐hour day.

A few days after Simon died, Dr Matthew reviewed the events of that night with Dr Piero Corti, an Italian missionary who, along with his wife, Dr Lucille Teasdale, founded St. Mary’s Hospital in 1961 and ran it for decades. Dr Matthew was his chosen successor.

The more Dr Corti listened, the more furious he became. He was exasperated by the gamble his protégé had taken.

”I wanted to strangle him,” said Dr Corti, who is 75. ”I was thinking of the future and that he was the man to take care of the hospital for the next 20 or 30 years. But I didn’t have the heart to tell him that. He had done what was normal for him to do.”

What was normal for Dr Matthew was a low‐key combination of geniality and unyielding resolve. He flatly refused to allow anyone or anything, be it messianic rebels or bleeding fevers, to destroy his hospital. To that end, he sometimes took chances that threatened his life, that bordered on recklessness. Yet he was such a solid medical man, such a devout Christian and such a nice guy that hardly anyone noticed his extraordinary appetite for risk.

For Dr Matthew, the first hint of an Ebola outbreak in Uganda came on Saturday morning, Oct. 7, when the telephone rang in his rented house in Kampala. At the time, he was temporarily living in the capital in order to finish up a master’s degree in public health. After nearly a decade of running a hospital in the middle of a civil war, he and his wife, Margaret, along with their five children, decamped from the north in December 1998 and moved to Kampala.

”There seems to be a strange disease killing our student nurses,” said the caller. It was Dr Cyprian Opira, who was phoning long‐distance from St. Mary’s Hospital, where he was acting medical superintendent.

The strange illness, Dr Opira said, had stumped everyone. The usual antibiotics did nothing. Stool cultures were not informative. A student nurse began bleeding from the mouth just as she died.

”We need your presence,” Dr Opira said on the phone.

Temporary escape from this kind of all‐consuming responsibility had been a precious fringe benefit of Dr Matthew’s leave of absence from St. Mary’s. He had taken the leave to study at Kampala’s Makerere University, telling his colleagues he would come back a better manager.

His wife rejoiced in the move. Kampala was 250 miles and a world away from the troubles of Gulu District and the endless responsibility of the hospital. For starters, there was no incoming artillery. At St. Mary’s, a year before the move to Kampala, a mortar shell bounced off a tree and punched through the roof of Dr Matthew’s house in the hospital compound. It crashed on the floor ‐‐ without exploding ‐‐ not far from the bed where he and Margaret were sleeping.

War was traumatizing the children, Dr Matthew told his wife, who couldn’t have agreed more. The move to Kampala also gave the doctor and his wife a vacation from the demands of his being a very big man in a very poor corner of Africa.

Gulu District, which borders Sudan, is part of Acholi land, a semiarid region of goats, cows and subsistence farms long neglected by the government of President Yoweri Museveni. Electricity, for example, is turned off in Gulu on weekends, and it often goes off during the week.

In the tribal calculus that shapes politics and patronage in Uganda and across Africa, the Acholi people are viewed by Museveni’s government as suspect. Museveni came to power in 1986 after waging a long guerrilla war against an Acholi‐dominated regime. During that war, Acholi soldiers murdered tens of thousands of Ugandans as part of a savage cycle of tribal killing that began in the 1970’s under Idi Amin, probably Africa’s most famous practitioner of brutal one-man rule. Museveni put an end to the killing and led Uganda into an era of rebuilding and relative prosperity. But Acholi land was largely left behind.

The lack of development and government services in Gulu District has been filled, in part, by successful Acholi men like Dr Matthew. His extended family, his clan and his tribe all made constant demands on his income, his influence and his kitchen. At their home in the hospital compound, Margaret usually cooked for about 20 people at each meal; eight sat at the dining‐room table, five sat in the kitchen and seven or so camped in the living room. Dr Matthew paid school fees for the children of many of his relatives. They came to him when they were sick. And if they died, he often paid to transport their bodies back to their home villages for burial.

The move to Kampala limited the importuning of the kinfolk. Margaret remembers their 22 months together in the Ugandan capital as the sweetest season of their married life. Dr Matthew loved being back in school, she said. It gave him a chance to study the latest techniques for managing the care of patients whose troubles ranged from poor hygiene to gunshot wounds to AIDS.

School had always been his salvation. He had grown up poor in the northern town of Kitgum, about an hour’s drive from St. Mary’s, with no strong kinship ties to the Acholi oligarchy in the Ugandan military. His father was a fishmonger who drowned when he was 12. His mother was a petty trader. She fed her four sons by smuggling Ugandan tea on her bicycle across the border to Sudan, where she traded for soap. She trained Matthew to be a bicycling smuggler, but it was in the classroom where he paid close attention. He was a phenomenal student, a permanent fixture at the top of his class in grade school, secondary school, university and medical school.

School had always been his salvation. He had grown up poor in the northern town of Kitgum, about an hour’s drive from St. Mary’s, with no strong kinship ties to the Acholi oligarchy in the Ugandan military. His father was a fishmonger who drowned when he was 12. His mother was a petty trader. She fed her four sons by smuggling Ugandan tea on her bicycle across the border to Sudan, where she traded for soap. She trained Matthew to be a bicycling smuggler, but it was in the classroom where he paid close attention. He was a phenomenal student, a permanent fixture at the top of his class in grade school, secondary school, university and medical school.

With a long string of scholarships as his rope, he pulled himself up from the lowest social rung in one of Uganda’s poorest regions to academic acclaim in the capital. Then he immediately returned to Acholi land.

When Matthew first showed up at St. Mary’s as an intern in 1983, Dr Corti, the Italian missionary, remembers that he and Lucille, a surgeon at the hospital, were amazed by the young doctor’s intelligence and gentle ability to lead. ”God sent that man here,” Dr Corti said. ”Within three months of his arrival, I told my wife that he is the one who can take over. She smiled and said she was thinking the same thing. People say we groomed him to run the hospital. He groomed himself.”

Dr Matthew left Uganda for a year in 1990 to take a master’s degree in tropical paediatrics at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. As usual, he graduated first in his class. Dr Bernard Brabin, who supervised his degree, said that of all the hundreds of young doctors from around the world whom he has taught in the past decade, Dr Matthew was one of the most impressive.

”First, it was a matter of ability,” Dr Brabin said. ”He had a highly critical intelligence that adapted very quickly to complexity. He expressed himself in clear, simple ways. We encouraged him to stay in the United Kingdom, to teach and pursue higher degrees. But his commitment was to the care of children in Uganda.”

Unlike tens of thousands of African professionals who leave the continent for better pay and better lives abroad, Dr Matthew apparently never even considered such a move. In letters he wrote from Liverpool to Dr Corti at St. Mary’s, he said not to worry about the hospital’s future; he would be back. Even if he was to get another advanced degree, he vowed, he would come back and do his research at St. Mary’s.

”Have you ever heard of a missionary temperament?” asked Dr Brian Coulter, a senior lecturer at the Liverpool School who knew Dr Matthew well and who visited him at St. Mary’s several times in the 1990’s. ”That is exactly what Matthew had. His aim in life was to minister to sick children and to run one of the few institutions that function efficiently in Uganda. That is what satisfied him, and that is what he wanted. ”While studying for his second master’s degree in Kampala, Dr Matthew insisted that his children take education as seriously as he did. He read to his twin 9‐year-old boys every night, Margaret said, and he pestered his son, Peter, 12, to work harder on math. For the first time in his life, he also had time to relax with his children, to follow British soccer on the BBC and to get a bit thicker around the middle.

”Have you ever heard of a missionary temperament?” asked Dr Brian Coulter, a senior lecturer at the Liverpool School who knew Dr Matthew well and who visited him at St. Mary’s several times in the 1990’s. ”That is exactly what Matthew had. His aim in life was to minister to sick children and to run one of the few institutions that function efficiently in Uganda. That is what satisfied him, and that is what he wanted. ”While studying for his second master’s degree in Kampala, Dr Matthew insisted that his children take education as seriously as he did. He read to his twin 9‐year-old boys every night, Margaret said, and he pestered his son, Peter, 12, to work harder on math. For the first time in his life, he also had time to relax with his children, to follow British soccer on the BBC and to get a bit thicker around the middle.

All this came to an end, however, when the telephone rang and Dr Matthew heard the words ”strange disease.” He left for the north at once, arriving at St. Mary’s Hospital in the early evening, in time to witness the death of a nursing student named Daniel Ayella. As the nurse died, the whites of his eyes turned red, and blood dribbled from his mouth. Dr Matthew had never seen anything like it.

”We thought it was something beyond our knowledge,” said Dr Yoti Zabulon, who stood beside Dr Matthew that night and watched the nurse die. ”We needed help.”

The following day, a Sunday, Dr Matthew told Sister Maria Di Santo, head of nursing at St. Mary’s, that he wanted to see the charts on all patients who had died strangely in recent weeks. He began drawing a map of suspicious deaths. It included 17 patients, two of them student nurses. Another student nurse was also gravely ill and would soon die.

That afternoon, community leaders from Gulu District came to the hospital. They told Dr Matthew that whole families were dying in their villages. They demanded something be done. Dr Matthew and Sister Maria stayed up most of that night, reviewing charts and comparing symptoms with C.D.C. and World Health Organization publications on infectious fevers that cause bleeding. Their suspicion and fear, Sister Maria said, was that it was Ebola. But they had never before treated or seen patients with the disease.

That afternoon, community leaders from Gulu District came to the hospital. They told Dr Matthew that whole families were dying in their villages. They demanded something be done. Dr Matthew and Sister Maria stayed up most of that night, reviewing charts and comparing symptoms with C.D.C. and World Health Organization publications on infectious fevers that cause bleeding. Their suspicion and fear, Sister Maria said, was that it was Ebola. But they had never before treated or seen patients with the disease.

What they read was based largely on what doctors had learned from the last major Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, Congo, in 1995, where 318 people got sick and 4 out of 5 of them died. The literature explained that close physical contact, especially unprotected exposure to an infected person’s body fluids, caused most new infections. The publications also explained that the sicker a patient becomes, the more dangerously infectious he or she is. Touching dead bodies, the literature said, was a major risk.

As Dr Matthew well knew, the dead‐body factor was especially alarming in Acholi land, where tradition demands that female relatives of the deceased work together to wash and dress a corpse. After a body has been buried, those in the funeral party wash their hands together in a common basin, joined by other mourners from the village. The tradition symbolizes solidarity, but during an Ebola epidemic it was a recipe for catastrophe.

”By morning it became obvious to Dr Matthew that it was some kind of haemorrhagic fever in our hospital,” Dr Zabulon said. ”He said, ‘Let’s go around the usual bureaucracy and call Kampala.’ ”

The call was taken by Dr Sam Okware, Uganda’s commissioner of community health services, who dispatched a team to Gulu from the Uganda Virus Research Institute. When they arrived to collect blood samples, Dr Matthew had already begun to move suspected Ebola patients into an isolation ward that he had set up following WHO guidelines.

Sub‐Saharan Africa is widely viewed as incapable of dealing with epidemics ‐‐ for example, AIDS. In countries like South Africa and Zimbabwe, where a fifth to a quarter of the adult population is infected, AIDS will kill around half of all 15‐ year‐olds, according to the United Nations. Around the world there are 16 countries where H.I.V.‐prevalence rates exceed 10 percent. All 16 are in Africa.

Uganda, however, happens to be a can‐do kind of place when it comes to public health disasters. It dropped off the United Nations list of countries most affected by AIDS because its government was the first in Africa to launch a substantial awareness campaign. It distributed millions of free condoms and relentlessly explained how H.I.V. is transmitted by sexual contact. The campaign is credited with lowering the infection rate to 8 percent, from 14 percent in the early 1990’s.

”Transparency, openness and modern communications, that is what we use,” said Dr Okware, the former head of Uganda’s AIDS control program who was quickly named chairman of its National Ebola Task Force.

When lab tests confirmed Ebola, the Ministry of Health contacted the who, the C.D.C. and major donor nations and called a news conference. It hired more than a thousand ”local informants” in 346 villages in Gulu District. They went from hut to hut, looking for sick people, who often were hidden by their families. Ebola burial teams were trained and outfitted with protective clothing. In parts of the district where the Lord’s Resistance Army is active, the army dispatched armoured personnel carriers to search for the sick and collect bodies. Ebola alerts filled the newspapers and state radio.

When lab tests confirmed Ebola, the Ministry of Health contacted the who, the C.D.C. and major donor nations and called a news conference. It hired more than a thousand ”local informants” in 346 villages in Gulu District. They went from hut to hut, looking for sick people, who often were hidden by their families. Ebola burial teams were trained and outfitted with protective clothing. In parts of the district where the Lord’s Resistance Army is active, the army dispatched armoured personnel carriers to search for the sick and collect bodies. Ebola alerts filled the newspapers and state radio.

”All dead bodies should be immediately buried in sacks made of polyethylene materials,” said one typically blunt public‐service announcement in a Kampala daily.

The campaign worked, but it also caused some panic. According to Dr Okware, rural people burned villages where Ebola was rumoured to be. Officials in neighbouring Tanzania and Kenya seemed to suspect that all Ugandans carried Ebola, screening them at the borders and sending hundreds home. Saudi Arabia banned Ugandans from the hajj. Even the Lord’s Resistance Army blinked, releasing 40 abductees it feared were infected.

Across northern Uganda, there was panic buying of Jik, a brand of household bleach manufactured in Kenya. Ebola burial teams used the stuff to soak sickbeds, douse bodies and sterilize themselves after a burial. As a result, some rural Ugandans worshiped Jik as a ”miracle drug,” according to Dr Paul Onek, director of health services in Gulu District. He said they kept a bottle around the hut as a talisman to scare off Ebola. People bathed in bleach and some drank it.

”I have heard that some of you are drinking Jik to stop infection right from the stomach,” Ronald Reagan Okumu, a member of Parliament from Gulu, said at a news conference on Oct. 30. ”Nobody should drink Jik.”

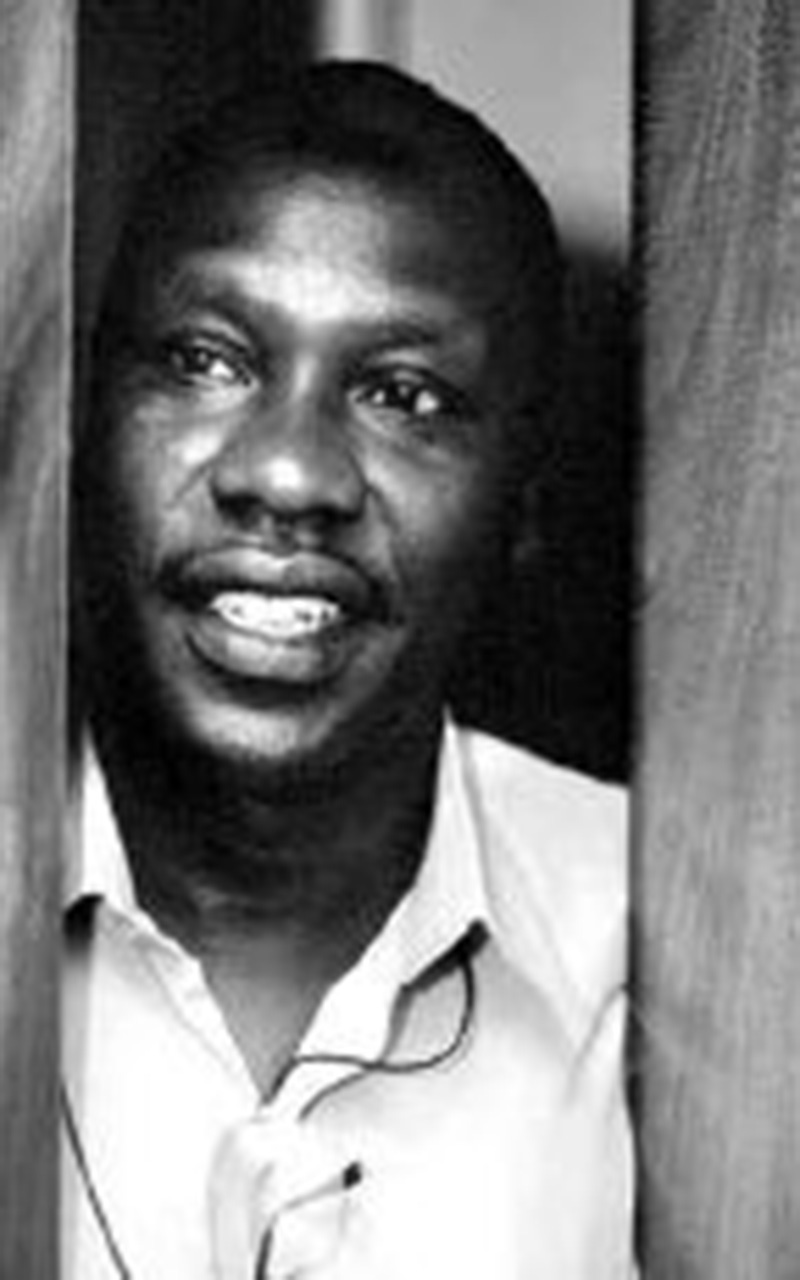

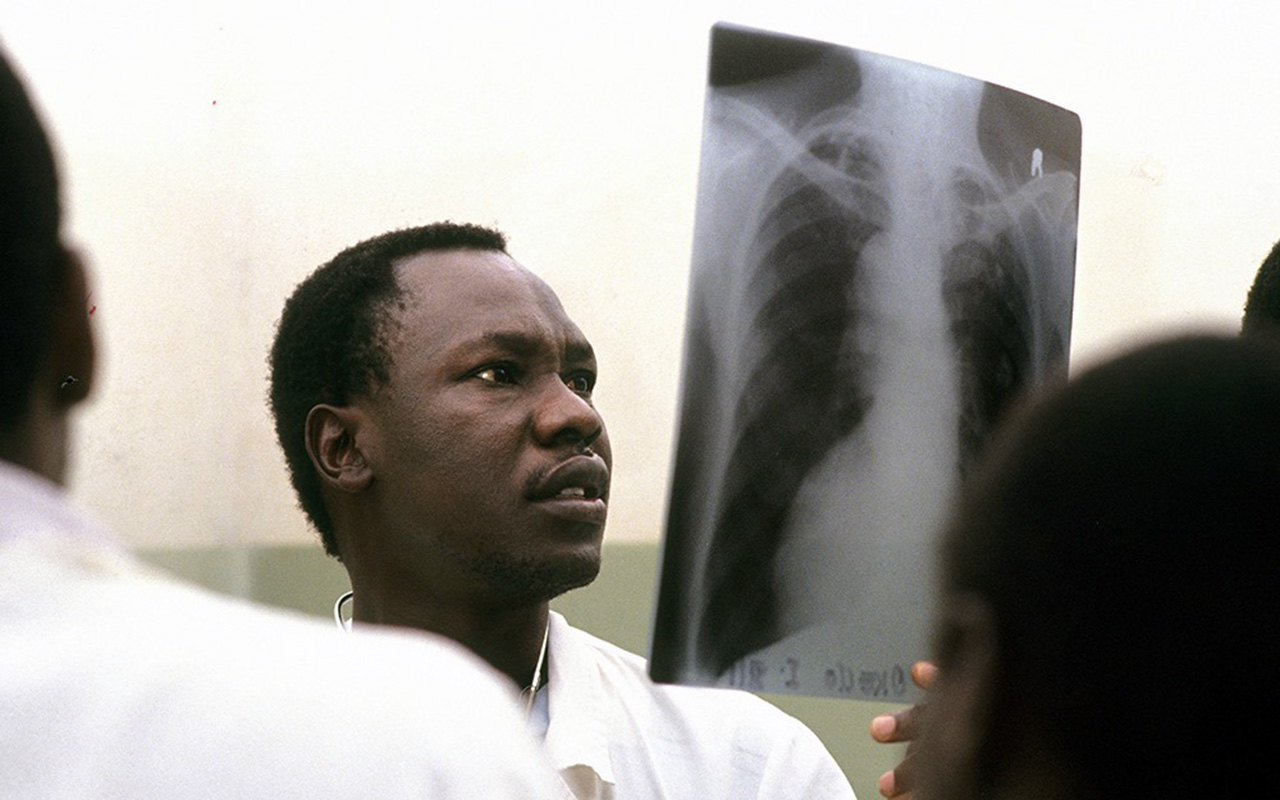

Dr. Matthew talking to the community at a camp

That same day, several hundred Acholi traditionalists took matters into their own hands in Gulu town. They tried to chase out the virus by shouting, running around with spears and beating on saucepans. They told Ugandan journalists they intended to exorcise the evil of Ebola and send it south toward Kampala.

The patient load at St. Mary’s soared in the week after Ebola was confirmed. By the third week of October, with the number of patients approaching 60, the three doctors, five nurses and five nursing assistants who had volunteered to work on the isolation ward were overwhelmed.

They could not handle the load, in part, because of the time and personal attention that they gave to each Ebola patient. In other African hospitals, the treatment strategy was entirely different. Doctors encouraged a spouse or family member to be the primary caregiver for each patient. Wearing protective clothing, caregivers cooked for and cleaned up after their loved ones. The system reduced risks for nurses and nursing assistants, keeping them away from infectious body fluids.

Dr Matthew, however, kept all kin away from infectious patients. He allowed only doctors, nurses and nursing assistants to go near them. His system helped contain the epidemic, reducing sickness and mortality rates among family members. At the same time, though, it placed health‐care workers in close quarters with highly infectious patients and increased their chances of contracting Ebola. Whether it was against rebels or viruses, Dr Matthew made a habit of taking personal risks for the sake of his hospital. In a pleasant but dogged way, he insisted that his nurses do likewise.

”There is no right answer to the question of how to nurse Ebola patients in Africa,” said Dr Daniel Bausch, a C.D.C. medical epidemiologist who worked in northern Uganda last fall and managed the Ebola ward at a small government hospital in Gulu town. In many African hospitals, it is less a matter of best medical opinion than of what is possible. Dr Bausch used family caregivers on the Ebola ward at Gulu Hospital because he said he had no reasonable alternative. St. Mary’s, though, had the facilities and the personnel to take on the care and feeding of Ebola patients without family help.

Whatever its medical or epidemiological value, Dr Matthew’s system became a management nightmare. He tried to reassure nurses and nursing assistants that the risk was tolerable. Yet as the weeks went by, Ebola insidiously eroded his authority. Health‐care workers wore their protective gear, they managed their risks and still they got sick. Twelve of them died.

”With each death, the tension built,” said Sister Maria. ”You could feel the atmosphere. It was building toward a climax. There were so many questions and no answers.”

To keep his volunteer nurses from bolting, Dr Matthew tried to lead by example. He was in the Ebola ward every morning at 7 and he finished up around 8 in the evening. As he made his rounds, he preached caution.

”Think with your head, not with your heart,” he shouted at one nurse in late October, when she rushed to clean up after a patient who had vomited on the floor. Dr Matthew instructed the nurse to douse the vomit with bleach before going near the patient.

In the evenings after leaving the isolation ward, Dr Matthew visited the many foreign doctors who had set up laboratories and were helping to care for patients at St. Mary’s, as well as at nearby Gulu Hospital. As they ate their dinner in the compound of his hospital, he questioned them about patient care, searching for ways to keep his nurses from getting sick. Dr Bausch, the C.D.C. medical epidemiologist who joined in these chats nearly every night for two months, said no one could give Dr Matthew a satisfactory reason why the nurses were getting infected.

In the evenings after leaving the isolation ward, Dr Matthew visited the many foreign doctors who had set up laboratories and were helping to care for patients at St. Mary’s, as well as at nearby Gulu Hospital. As they ate their dinner in the compound of his hospital, he questioned them about patient care, searching for ways to keep his nurses from getting sick. Dr Bausch, the C.D.C. medical epidemiologist who joined in these chats nearly every night for two months, said no one could give Dr Matthew a satisfactory reason why the nurses were getting infected.

”Very few of these nurses had ever been in a situation where they had to put on gowns, gloves, masks and wash their hands after every contact with every patient,” said Dr Bausch. ”Dr Matthew was in a situation where he had no choice but to herd around inexperienced people who didn’t want to be there.”

The pressure on him was unending. But Dr Bausch said that through it all Dr Matthew was ”a very kind, very mild‐mannered guy who liked to make jokes,” especially about the endless American presidential election. ”He didn’t seem as stressed as a lot of people would have been.”

Privately, Dr Matthew was afraid ‐‐ for himself and for the hospital. He did not want his wife or his children to come near him. On Oct. 14, he wrote to Margaret in Kampala: ”I will not be able to come to you there because we are very busy, and secondly because it would be dangerous to you, in case I am incubating the disease, although it is very unlikely. You should not also come here! The situation is very bad.”

The situation in the hospital became a whole lot worse in late November. By then, the national Ebola epidemic had peaked, and the number of new cases was beginning to fall. Not so for patients and nurses inside St. Mary’s.

During a 24‐hour period that ended at dawn on Nov. 24, seven people died of Ebola, including three health‐care workers. Two of these workers were nurses who did not work in the Ebola ward. By breakfast, news of their deaths was causing panic. If nurses who stayed away from the isolation ward could die, it seemed that anyone could die. Nurses mutinied. The day‐shift staff did not show up for work. Instead, at 8:45 a.m., about 400 health‐care workers, nearly the entire staff at St. Mary’s, packed into the assembly hall of the hospital’s nursing school.

”We were very many and we were so scared and we were a bit aggressive somehow,” said Margaret Owot, a nurse who attended the meeting and who worked on the Ebola ward. ”Ebola was a disease that no one knows how it is killing, and the nurses thought everybody would die.”

When Dr Matthew heard about the meeting, he rushed to the assembly hall and demanded to know what it was that the nurses wanted.

”We are thinking that the hospital should be closed,” one nurse shouted.

By this time, Dr Matthew was well versed in the art of persuading frightened health‐care workers to swallow their fear. He had made a series of inspirational speeches at staff meetings and funerals. At the largest of those funerals, for an Italian nun who died of Ebola, he had spoken on Nov. 7 of the responsibilities of love.

”It is our vocation to save life,” he said then, in a talk recorded by the Rev. Matthew Odong, the vicar general of the Catholic archdiocese of Gulu and Dr Matthew’s longtime friend. ”It involves risk, but when we serve with love, that is when the risk does not matter so much. When we believe our mission is to save lives, we have got to do our work.”

But on the morning of the mutiny, which happened to be his birthday, Dr Matthew apparently concluded that inspirational rhetoric would not keep the hospital open. So, he used threats. ”If the hospital is closed, I will leave and I will never come back to Gulu,” he said, according to Owot.

He had their attention.

With the assembly hall stone silent, Dr Matthew told the nurses, most of whom he had helped train, the story of how he had volunteered to be kidnapped by the Lord’s Resistance Army. He had been afraid the rebels would kill him, but he took the risk to protect the hospital and keep it open for patients who had no place else to go.

The kidnapping tale laid out the principles that governed his life and the circumstances under which he was willing to risk losing it. By telling the story, he challenged the nurses to live, and perhaps to die, by the values that had brought them into nursing in the first place.

If you abandon the hospital because of fear, he concluded, many patients will die, and you will be responsible.

”For me, I felt that he gave us really a fatherly word,” said Owot, a nurse who has worked at St. Mary’s for 16 years. ”He made me see that if the hospital is closed and I fall sick, where would I go? who would nurse me?”

At another long and contentious staff meeting in the same hall that afternoon, Dr Matthew shifted back to inspiration, which was much more his style. He could not force them to stay, he said, but he would continue fighting Ebola, alone if necessary, until the virus was beaten or until he was dead.

He joined the nurses in a song. The mutiny was over.

That evening, his wife called him, and all his children came on the line to sing ”Happy Birthday.” But Dr Matthew was exhausted. ”Margaret, I cannot talk,” he told her. ”I need to rest.”

A total of 29 health‐care workers contracted Ebola in Uganda, and 17 of them died, according to the C.D.C. Exactly how any of them got infected is not known with a high degree of certainty. But there is a consensus among doctors who worked in Uganda, as well as in Congo during previous Ebola outbreaks, about how the infection is not spread.

A total of 29 health‐care workers contracted Ebola in Uganda, and 17 of them died, according to the C.D.C. Exactly how any of them got infected is not known with a high degree of certainty. But there is a consensus among doctors who worked in Uganda, as well as in Congo during previous Ebola outbreaks, about how the infection is not spread.

Simply breathing in the vicinity of people who are infected with Ebola is unlikely to make you sick. Ebola is not a ”free virus” that floats around for hours in the air of an isolation ward. ”There has to be a real line of transmission,” Dr Bausch said. That means direct contact with body fluids, like vomit, blood or sweat. But the experts agree that a coughing patient who is spraying mucous or blood into the air is also a threat.

”It is not known if this spray landing on bare skin is enough,” said Simon Mardel, a who consultant who often made rounds with Dr Matthew. ”It seems most likely that there must be a break in the skin. When a patient coughs, a much more likely route of inoculation for a health‐care worker is the mouth, the nose or the eyes.”

Experts guess that many of the health‐care workers who got sick in Uganda made a small mistake. Their protective clothing, in the equatorial heat, may have made them uncomfortable or claustrophobic. After touching a patient, they may have gotten careless and slipped a gloved finger inside their protective mask to scratch an itchy nose or rub a sweaty eye.

Almost none of the health‐care workers in Uganda wore goggles at all times inside the isolation wards. They quickly fogged up. As a result, a nurse couldn’t find a vein for a blood sample. A doctor couldn’t see a patient’s face or read a chart.

”I would have my goggles on, but if I got close to a patient to listen to his lungs, I would put my goggles down,” said Dr Bausch, who makes his living by working around the world’s most infectious viruses and describes himself as ”incredibly careful.”

During the epidemic in Uganda, complaints about foggy goggles resulted in shipments of, among other things, plastic face shields that look like upside‐down hockey masks. They did not fog up like goggles, but they were far from perfect. Open at the top, they left room for particles of coughed blood to drift down into the eyes.

Like most of the doctors and nurses, Dr Matthew did not always wear eye protection. Babu Washington Stanley, the night‐shift nurse who called him out of bed on Nov. 20, the night Simon Ajok erupted in blood, clearly remembers that the doctor did not put on goggles or a plastic face shield that night.

Although no one can be sure, this lapse may have been what infected Dr Matthew. In his rush to help a dying nurse whom he had helped train, he violated his own rules. He thought with his heart.

Two days after his birthday, on a Sunday Night, Dr Matthew called his wife. She was startled by the sound of his voice. He was heavily congested and coughing.

”Margaret,” he said, ”I have a terrible flu.”

Monday morning, he had a fever. At the hospital infirmary, he told Sister Maria he had malaria. She agreed it must be malaria.

”We said malaria, but we thought Ebola,” Sister Maria said.

The fever grew worse as the day went by. He cancelled meetings and went home to bed. By Tuesday, antimalarial drugs had not brought down his fever. By Wednesday morning, he was vomiting, and he found it difficult to keep liquids down. Dr Pierre Rollin from the C.D.C. ran blood tests. They were done at a lab on the hospital compound.

That night, Grace Obuu, 24 became a nurse at St. Mary’s after Dr Matthew and his wife adopted her, went to his house. He was alone, and she put him on an IV drip to help keep him hydrated. His fever was high, and he was very weak, the nurse said, but he had stopped vomiting. She was startled by the sound of his voice. He was speaking loudly and distinctly, and he was not talking to her.

”Oh, God, I think I will die in my service,” he prayed. ”If I die, let me be the last.” Then, in a powerful voice, he sang ”Onward Christian Soldier.”

Two years earlier in a Pentecostal church in Kampala, Dr Matthew had delighted his born‐again wife by raising his hand and announcing to the congregation that he, too, was born again. Always a churchgoing Protestant, he had since been going to church twice a week, until the ”strange disease” called him away from Kampala.

Two years earlier in a Pentecostal church in Kampala, Dr Matthew had delighted his born‐again wife by raising his hand and announcing to the congregation that he, too, was born again. Always a churchgoing Protestant, he had since been going to church twice a week, until the ”strange disease” called him away from Kampala.

The blood test came back positive for Ebola.

”When I told him, he himself asked to go to the isolation ward,” Dr Rollin said. ”He said, ‘Since I am the boss, I should show an example.’ ”

A telephone call was finally placed on Thursday afternoon to Margaret, who had heard nothing since Sunday night. Dr Matthew had not wanted her called, saying he feared that she would take the call on her mobile phone while driving in traffic and would get in a wreck.

She was sitting on a sofa at home when the phone rang. She immediately packed her bag, hired a taxi and left for Gulu. But she was late reaching an upcountry bridge across the Nile River. Soldiers block it at night as a security measure against the Lord’s Resistance Army. Margaret had to sleep in the taxi.

On Friday morning at 9:30, dressed in protective gear, including goggles, she approached her husband’s bedside. He was in Room 4 in the Ebola ward, next to the room where Simon Ajok died 11 days earlier. At the sight of him, Margaret began to cry, and she rushed toward his bed to hug him.

”Don’t you come close to me!” Dr Matthew warned. ”You will get infected.”

He called a doctor, who brought Margaret a stool. She sat about three feet away.

”You can’t stay here when you are crying,” he told his wife. ”You will get infected. You don’t have to cry. You have to be strong and only pray.”

She stopped crying. He asked her how the children were doing in school. He was particularly worried, she said, that Peter was not paying proper attention to math.

After about 15 minutes, he seemed tired, and she left. That evening, he was stronger, as Margaret remembers, and his eyes were clear. He said that he probably got Ebola from Simon Ajok, and he struggled to explain why he took the risks that made him ill.

”Look, Margaret, it is a rough time, I know,” he said. His wife recalled his words with reverent precision, as if she were reciting from Scripture. ”You were not expecting this. God’s will is not our will. I did not also expect to get, you know, infected. But being a person working in the foreground in this place, anything can happen. A mechanic can get his hands chopped off in a machine. Even a woman when she is cooking can get burned. So, you just have to accept the situation.”

Margaret became angry. ”Now I can’t even touch you,” she told him. ”I can’t even nurse you. I can’t do anything. I just have to sit aside like a traitor.”

”You have to accept your fate,” he replied. ”I don’t want you to get infected. If anything happens to me, at least you will be alive to look after my children.”

On Saturday, his breathing was worse. He found it difficult to speak. Ignoring his warnings, Margaret moved close enough to touch her husband through the four surgical gloves she wore on each hand. During her 20‐minute visits, she held his foot.

Dr Matthew was getting weaker by the hour, exhausting himself as he fought for breath. On Sunday afternoon, his doctors asked Margaret’s permission to put him on a respirator. She gave permission, but before the machine was hooked up, she went to his bedside and asked him to pray with her.

”I said, ‘Be strong, fight this sickness with the blood of Jesus,’ ” Margaret said.

He complained that he was dry and, until the doctors shooed her away to hook up the respirator, she slipped ice cubes into his mouth with her gloved fingers.

The breathing machine seemed to be the answer. When Margaret left her husband’s bedside early Monday evening, his fever had come down, the oxygen level in his blood had risen and his pulse was near normal. One doctor told her it was a miracle. Late Monday night, however, his lungs haemorrhaged. This was the worst‐case scenario his doctors had feared, and they could do nothing.

Dr Matthew died at 1:20 a.m. on Dec. 5. By the time Margaret was notified and ran to the Ebola ward, he had been zipped up in a polyethylene body bag. She asked that it be unzipped just a little so she could see his face for the last time. The corpse, she was told, was too infectious. The answer was no.

Doctors who treat Ebola are not convinced that they have a whole lot to offer any patient. They estimate that using IV drips to replace lost fluids might make a difference for about 10 percent of those who get sick. For others, they guess, the seriousness of the illness depends on the genetic makeup of a patient, the amount of tainted blood or other body fluid that has come in contact with a patient and the route of infection. The prick of a bloody syringe, for example, is almost certainly worse than a cough in the face.

It also depends on the strain of the virus. In Congo in 1995, about 80 percent of those infected with Ebola died. But the strain of the virus that the C.D.C. isolated in northern Uganda was different from what they found in Congo and considerably less deadly

It was identical to a strain that caused two Ebola outbreaks in nearby southern Sudan in the late 1970’s. There, in a place where medical care was all but nonexistent, the death rate was around 50 percent ‐‐ roughly the same as it was last year in the best Ugandan hospitals. The numbers suggest that modern medicine, at least so far, is helpless to change the rate at which the various strains of Ebola kill human beings.

”Ebola is a tough disease,” Dr Bausch said. ”I am not so sure that once someone is infected that the treatment we offer prevents more people from dying than would have died anyhow. The saddest example of that is Dr Matthew. When he got sick, people pulled out all the stops. But it didn’t matter.”

Ebola is also finicky, depending on who gets infected. The same viral strain, acquired in the same way on the same evening, from the same infectious patient, can kill one person, while giving another a headache. Babu Washington Stanley, the night‐shift nurse, also got sick with Ebola nine days after he and Dr Matthew struggled to care for Simon Ajok. Stanley, though, came down with the mildest case of Ebola on record in Uganda. He had a headache for a few days, and then it went away. Ebola made him hungry, he said, especially for liver. Now he is fine.

There is an amateur videotape of Dr Matthew’s burial. It is almost unbearable to watch.

According to a will he wrote in the Ebola ward in the days before his death, a grave was chosen inside the hospital compound beneath a towering banyan tree. It lay beside the grave of Lucille Teasdale, the surgeon who was the wife of Dr Corti. Dr Teasdale, who died of AIDS she contracted while operating on patients at St. Mary’s, had been Dr Matthew’s mentor, champion and great friend.

According to a will he wrote in the Ebola ward in the days before his death, a grave was chosen inside the hospital compound beneath a towering banyan tree. It lay beside the grave of Lucille Teasdale, the surgeon who was the wife of Dr Corti. Dr Teasdale, who died of AIDS she contracted while operating on patients at St. Mary’s, had been Dr Matthew’s mentor, champion and great friend.

Since his body was highly infectious, he was buried the day he died. An Ebola burial team, dressed in protective gear that seemed suitable for a lunar landing, rolled up to the grave site at 4 p.m. in a white ambulance. They whisked a simple wooden coffin out of the ambulance and lowered it into the grave with ropes. All the while, one member of the burial team sprayed the coffin, the ropes and his colleagues with Jik bleach. More a disposal procedure than a burial, it was over in less than five minutes.

On the videotape, the moment the ambulance comes into view, the soundtrack explodes with the screaming of nurses. Ear‐splitting and inconsolable, in voices that fused grief, exhaustion and rage, their shrieking was the hopeless music of the funeral. The nurses were part of a crowd of several hundred people who had been warned to stay well away from the grave until it was covered with dirt.

Margaret stood at a distance with her children. She had insisted that they witness the burial. Otherwise, she believed it would be impossible for them to accept their father’s death. They arrived from Kampala just 30 minutes before the service.

Margaret stood at a distance with her children. She had insisted that they witness the burial. Otherwise, she believed it would be impossible for them to accept their father’s death. They arrived from Kampala just 30 minutes before the service.

Many government officials, including the minister of health, had also rushed north to Gulu. During the height of the Ebola epidemic last fall, Dr Matthew had been quoted almost daily in the Ugandan press. He had become a national icon: the fearless field commander at the centre of a biological war that threatened everyone in the country. Even though the Ebola outbreak had been all but defeated by the time he died, Dr Matthew’s death rattled the country’s self-confidence, suggesting somehow that the centre could not hold.

For a time, the doctor’s death paralyzed Uganda’s fight against what was left of the Ebola epidemic. St. Mary’s Hospital stopped admitting new Ebola patients. Across Gulu District, a number of health‐care workers quit. Suspected Ebola patients refused to be taken to hospitals. According to Dr Onek, the health officer for Gulu District, local people were asking, ”Why go to the hospital, if the big doctor has died in the hospital?”

Six weeks after the funeral, during a long and mournful conversation about the consequences of Dr Matthew’s death, Sister Maria said St. Mary’s had not yet recovered, and she doubted that it ever would. The hospital has not been able to find a new medical superintendent.

”You know, so many people relied on him,” she said. ”He had clear ideas about what to do with the future of the hospital. We have lost a guide. He was so clever in a way of talking to you kindly. He could lead people. That is what we have lost.”

Margaret, too, felt lost. President Museveni praised her husband’s courage and promised her about $2,800 as a special death benefit. But that would not be nearly enough, Margaret said, to finish building a house in Kampala or to send five children to university, as her husband had planned. She said she did not know how she would be able to honour his wishes.

The doctor who made the mistake of thinking with his heart left far more behind than a vacuum.

Epidemiologists who travelled to Gulu credit Dr Matthew with helping to contain Ebola before it could spread. His insistence on immediately calling senior health officials in Kampala jump‐started the government’s public‐awareness campaign. He may have saved hundreds, perhaps thousands, of lives.

As important for containing future outbreaks, C.D.C. virologists said his support for their research means that Uganda’s epidemic should produce more scientific data on Ebola than all the other outbreaks in Africa combined.

”If you need it, you have it,” Dr Matthew told foreign researchers when they descended on Uganda, according to Dr Rollin.

Access to St. Mary’s laboratories allowed researchers to preserve a vast number of blood samples from Ebola patients at every stage of infection. The samples could help them discover how Ebola triggers a cascade of immunological events that turn the body’s defences against itself, transforming white blood cells into subversive agents that trigger bleeding. The samples could also help them understand ‐‐ and perhaps one day invent a drug to inspire ‐‐ the remarkable immune response that allowed Babu Washington Stanley to shake off Ebola as if it were a mild hangover.

Father Odong, the vicar general of Gulu, said that he hoped his friend’s story will offer his fellow Africans a new definition of what it means to be a big man in Africa. ”It is not about getting rich and having power,” he said. ”We should tell everyone the story of Dr Matthew.”

Whether or not his story survives, its last chapter did turn out as Dr Matthew had hoped.

His hospital and his nation defeated Ebola, at least this time around. With no new cases in the previous 21 days, who declared on Feb. 6 that the epidemic was effectively over. The isolation ward at St. Mary’s has been closed and scrubbed down and will reopen this month as a children’s ward. And Dr Matthew’s solitary prayer in the week before he died was answered: among the health‐care workers who fought Ebola at St. Mary’s, he was the last to die.